As David Bowie’s death, just days following his 69th birthday, shook millions of people across the world, the outpouring of sadness at losing such a multi-skilled giant of music was underpinned by a multitude of memories. A veritable rainforest of printed articles and tributes and vast swathes of the Internet and social media have burst forth about one of the most influential creative figures of the past half-century.

As David Bowie’s death, just days following his 69th birthday, shook millions of people across the world, the outpouring of sadness at losing such a multi-skilled giant of music was underpinned by a multitude of memories. A veritable rainforest of printed articles and tributes and vast swathes of the Internet and social media have burst forth about one of the most influential creative figures of the past half-century.

I did not expect to be asked to add my two-penny-worth to the reminiscences of the great and the good, other than in the many phone conversations in the days following Bowie’s death. As a counter-terror expert I am usually asked by the press or specialist media to write or comment on a terrorist bombing or some such. I have also tended to avoid talking about celebrities – while harbouring deranged dreams of becoming one myself – until Marija kindly invited me to describe the influence Bowie had on me. Yet another one, I thought. Who am I to comment on such a tumultuous figure? But you could almost excuse the self-indulgence of the tributes as this was no ordinary singer, no ordinary celebrity, with no ordinary influence. Bowie had a disproportionate effect on those who followed him and their stories all form a vast body of evidence to how he was the ultimate catalyst in their lives.

Oppenheimer Analysis on stage in 2010

But what could I add to this tsunami of tributes? His effect on my identity and sexuality? Immeasurable. Reason for meeting my first great love in London, with whom I’ve enjoyed a 40-plus-year wonderful friendship? No question: I would never have met Jane were it not for Bowie. Stage image? Undeniable. Music? I would never have met Martin and us form Oppenheimer Analysis were it not for Bowie. Neither would I have had so many changes of image later. So the memories come flooding in, and the enormity of effect of that one ultra-special person whom I never knew (how many have said that). So it is with some trepidation, and hoping these edited highlights will add a few atoms of value to the British Library-sized catalogue of reminiscences, that I share a few diary snapshots from a 40- year Timeline of Effect that a vast supernova of a star has had on a very minor planetoid.

1969

I hear the first extraordinary hit Space Oddity at school after a childhood obsessed with space. Just before the first moon landing. I like it but am still mired in a decade of ‘60s pop, soul and rock. I recall it later as predictive – when Apollo 13 almost doesn’t make it back…

1973

At university and Bowie and his music passes me by. I hear and dance to Ziggy tracks at student discos in Liverpool but am more into the ‘heavy’ music of the time.

1975

Bowie appears on my TV screen now I am six months into a riotous life in London. At my third address in so many months I watch the award-winning TV documentary, Cracked Actor, made during the Young Americans period just before Bowie’s first film. Scales fall from eyes and I now know what I want to be. Androgynous, bisexual, red-haired – the whole enchilada. But not yet a singer.

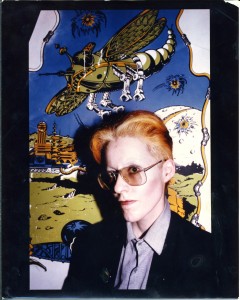

I go to a posh hairdressers’s in Bond Street and get my jet-black ship’s-cable hair bleached and dyed by a stylist who adores Ziggy and thinks I want that style. I show her pictures from Young Americans and emerge with a new orange and blond head in the manner of the Man Who Fell to Earth. I walk out, flame-haired, into Bond Street and the traffic stops, horns hoot, and I am higher than the stars. As so many have written, Bowie is the Great Liberator of outsiders floundering down here on Earth.

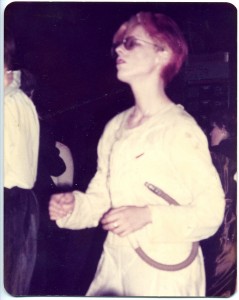

Photo: At Studio 21 in central London in 1979.

1976

I buy Station to Station as my first Bowie album, which is spellbinding. The discipline, distance, and coldness of it is perfect. My Northern Irish friend at work, Vince, takes me through all of Bowie’s albums and I buy all the rest. Hunky Dory for lovely songs and Diamond Dogs for apocalyptic decadence are my other favourites, with Young Americans as I love the plastic soul period and look.

The film is out and I go with a succession of friends and colleagues to see it and am totally at one with the character, having read the wonderful book by Walter Tevis as well. I walk into work in the full movie gear. The sharp intake of breath from colleagues is audible.

I’m told by my boss that I should leave and get a career in the media. Remember, this is early 1976 and I’m a not-so-Naked Civil Servant. My mum has even had the black duffel coat made for me by a little Jewish tailor in Leeds in the exact style. But both parents hate the hair and the direction I’m going in with regard to sexuality and all that nonsense. So good job I’m in London for life. I buy or make every item of clothing from every scene. Every suit, every hat, every coat – as a collector and lover of clothes this is a wonderful challenge.

I’m told by my boss that I should leave and get a career in the media. Remember, this is early 1976 and I’m a not-so-Naked Civil Servant. My mum has even had the black duffel coat made for me by a little Jewish tailor in Leeds in the exact style. But both parents hate the hair and the direction I’m going in with regard to sexuality and all that nonsense. So good job I’m in London for life. I buy or make every item of clothing from every scene. Every suit, every hat, every coat – as a collector and lover of clothes this is a wonderful challenge.

It’s a Saturday and I’m walking through Portobello Road market. I notice some kids are following me. I let them catch me up and one says in a French accent: “where is your show and where can we buy your album?” And it doesn’t click until I see their gawping faces and… it can’t be… surely they don’t think I’m… him….? Once I put them right in this regard it doesn’t seem to disappoint them that I’m not the real thing. So I take them to a pub and buy them a drink.

Photo: In Man Who Fell to Earth mode at a science fiction convention in 1978, propped up against a jukebox.

1977

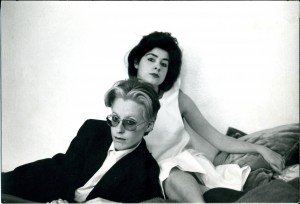

DJing at a gay club in London, done up in Thin White Duke mode. A beautiful young girl with a mass of dark curly hair and – in the midst of the scruff and punk of the time, dressed in a Hollywood-style fur coat and pleated dress – comes up to me at the turntables and asks if I will go for a drink. She tells me how much she loves Bowie, exclaiming: “But I’m not your fan!” She has followed him from childhood, has been to every Ziggy gig, and adores him unreservedly.

Jane and I are to enjoy eight wonderful years together as an extraordinary rendition of the Man Who Fell to Earth and Mary Lou -and a lifetime of friendship. We see Bowie live at Wembley. Most of the lookalikes are still Ziggy. Jane and I are constantly photographed and yelled at in a capital that’s always in a hurry.

I go back up to Liverpool for the day and walk through Lime Street station to get a cab. One of the cabbies yells out, “The Moon’s that way.” I reply, “that’s all right mate – I only want to go to Walton.”

With my girlfriend Jane Moloney in 1977, who adores Bowie to the nth degree. She’s the one on the right.

1978

I get a new job with a glossy American science/science fiction magazine, Omni. When I ask my boss why I got the job over others with science degrees, he says: “You looked and acted the part for a futuristic magazine – and the others were boring.”

1979

Jane and I and a host of Bowie fans and friends hit the nightclubs – Blitz and Studio 21 – a much friendlier club where we can pose and dance to a perfect combination of Bowie and an emerging synthesizer-based type of music, electro. The New Romantics have arrived, and for two years we are photographed for artists’ exhibitions and The Face magazine and I can’t remember how many others. A nightclub friend and hairdresser Ricky renews the Newton hair every two weeks with enough hydrogen peroxide to blow up the centre of London.

The magazine I work for sends me to a science fiction convention in Brighton. I’m at a hotel party for the authors when an older, slightly Lennonesque man approaches me, wide eyed. This is Martin Lloyd, who says how much he has adored Bowie despite a very straight upbringing and how he’s never seen anyone look more like him. We become friends.

Oppenheimer Analysis: Martin takes a picture of me in the reflection of a car during a trip to Brussels to play live on invitation of Lieven de Ridder

1981

Martin invites me to write some songs as he has set up his own home recording studio in Battersea and has begun working with vocalists. I start writing lyrics while being driven around London from one work assignment to another. The first song we record is Behind the Shades – a direct reference to the Man Who Fell to Earth, sitting in his blacked-out car. We call ourselves Oppenheimer and add Martin’s name Analysis from when he recorded with Dave Rome.

1982

We go on to record a very long song, New Mexico, which for me heralds the melding of the Bowie movie alien into another very different, but strangely similar, outsider: Oppenheimer, the Father of the Atomic Bomb. My stage image is still a Bowie inspiration: mired in the cold war and a perfect morphing from the alien Newton to the ethereal scientist Oppenheimer, who despite building the Bomb for America is booted out of government and consigned to being an outsider. Newton is similarly discarded and maltreated as a threat to national security. Both Newton and Oppenheimer are rooted in New Mexico. Oppenheimer on stage is another very thin, pale, sharp-suited, hat-wearing, chain-smoking genius, and I am totally at home playing the role. Being only around 110 pounds (50 kilos) in weight helps. The Thin White Duke, the Thin White Nuke.

Martin and I play our first gig at The World David Bowie Convention at the vast Cunard Hotel, Hammersmith, in front of thousands of Bowie fans, and organised by the publishers of Starzone, a Bowie fanzine. I hardly sing a note in tune and sign more autographs – many, on request, and to my amazement, on Bowie’s image on the front of the event programme – than at any other gig or event to follow.

1992

I go on one of many trips to Los Alamos, New Mexico, birthplace of the atomic bomb. Bearing the name Oppenheimer with a strong acquired resemblance to the original along with a growing expertise in nuclear weapons guarantees me a sort of freedom of the city. I tell a friend who organises trips to the lab and the stunning scenic surroundings about Bowie and my Man Who Fell incarnation. She tells me: “we were all in that film – it was made here.” And did I want to go to the lake where his spaceship crashes down, as it’s only a ten-minute drive away? So we arrive at the lake, which is spellbinding. I take photos, which I still have. If only I’d been here and seen this back in 1976…

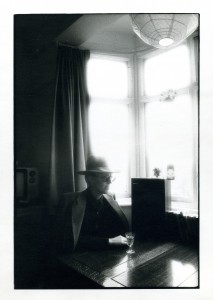

Photo: Photographed at home with the final scene of the film in mind.

2005

Martin and I are back on the gig circuit, having re-formed Oppenheimer Analysis after I receive emails about the ‘New Mexico’ album, made on cassettes over two decades earlier. I am now an independent analyst and writer on weapons of mass destruction, terrorism and defence – to add to the stage image, now the ‘day job’ is a 21st-century post-Cold War rendition of Oppenheimer. We record our first song together for 20 years, Fellow Traveller, with beautifully played acoustic guitar by Martin which is directly influenced by Space Oddity and Starman.

2010

On the day of the last Oppenheimer Analysis gig in Berlin we go on a little tour round the Hansa studios where Bowie made Heroes. Martin is the happiest I’ve seen him. One of our great friends, Mark Warner from Sudeten Creche, is with us and I chat with him walking round the Brandenburg Tor about doing some songs together, which forms the start of our band Touching the Void.

Left photo: Oppenheimer Analysis on stage in 2010

Righ photo: With Martin at the Hansa Studios in Berlin in 2010

2013

Fellow Traveller is played at Martin’s funeral, a day of great sadness. I hear, for the last time, his beautiful opening guitar chords as pure Bowie.

2014

With my other band Oppenheimer MkII, formed in 2012 with Mahk Rumbae in Vienna, we decide to record a Bowie cover. I choose Be My Wife from the Low album and Mahk gives it a whole new electronic treatment, while I make a valiant effort at singing in a London accent.

https://soundcloud.com/oppenheimermkii/be-my-wife

2015

I have not been listening to new Bowie work but have played favourite old tracks on my Mixcloud show, the Oppenheimer Time Machine. The influence is but a distant memory.

2016

2016

Bowie dies. I immediately think of my ex, Jane – and we talk on the phone about how much he affected our lives. She is devastated. Then I see her photographed by press agencies at the Bowie memorial gathering in Brixton, south London. She is shown laying flowers at the Ziggy memorial, with that glorious Aladdin Sane tattoo on her back. The photos go viral. I am so pleased she has gone there on that day.

Jane at the Bowie memorial gathering in Brixton, south London, the day after he died

And as for the music, I keep thinking how much I keep changing image in life, and in all three bands I’m involved in: playing roles is one of the greatest influences Bowie has had, to be able to morph from space alien to scientist, spy, sniper, and who knows whatever else I dream up.

Mark Warner suggests we do a cover of Heroes for our next Touching the Void album. This will be the greatest honour and the ultimate challenge. Everything has come full circle, and all we can do now is give thanks to one who has not only inspired us in our work but changed our lives, as he did mine, in ways that cannot even begin to be detailed here. So much more than a hero.

Left photo: An artist we knew made this image of me in 1979, which may look somewhat eerie now…

Right photo: Oppenheimer Analysis on stage in 2010

Article written by Andy Oppenheimer