Since its formation in 1980 in former Yugoslavia, Laibach has become one of the most influential bands in pop culture. They were often banned and censored since their inception by the Yugoslav regime, but they still reached the international fame. After 40 years of continuous achievements, 30-something music releases, thousands of shows around the world and numerous other artistic endeavours, we finally had the opportunity to talk with Laibach about their rich and prolific career.

1. Laibach was formed in Trbovlje, Slovenia, former Yugoslavia, in 1980. 40 years later, an impressive discography, countless shows all over the world and other achievements under your belt, what would you say you owe your long career to?

Laibach: To a large extent, time is more and more on our side, but we also have some good ideas and nothing better to do than release them persistently.

2. Former Yugoslavia was a very particular country, geopolitically, historically and culturally. When you started, its ideology was nearing exhaustion and it was trying to reinvent itself. Could you explain your early work in that context, the imagery and messages vs. the ideology?

Laibach: We basically did the same as the leading ideology on power did. We used the same images and the language that was imposed on us. In a way we were the carbon copy of Yugoslavia. We didn’t invent anything original except maybe the method (of over-identification), and even that we found in the roots of the system itself.

3. Laibach was designed as a system which replaced individual identity with collective consciousness and anonymity. It derived its ideological premises from industrial production and totalitarianism, while music was a vehicle for delivering the ideas and thus was made secondary. Laibach also used different means of media to communicate, which all served as Laibach propaganda. Why was Laibach’s work based on such propositions?

Laibach: We started as a collective, we acted as a collective and therefore we functioned as a collective – according to industrial production and totalitarianism. We believe that art and totalitarianism are not mutually exclusive and that totalitarian regimes abolish the illusion of revolutionary individual artistic freedom. We also believe that all art is a subject to political manipulation, except for that which speaks the language of this same manipulation. In this respect we are not much different than the Beatles and other music groups. Music for us was always a vehicle for delivering ideas, but that does not mean that music was secondary; most of the time music itself was the leading idea.

4. Slovenia was a meeting place of West and East Europe and, in that sense, an interesting and inspiring setting for a project such as Laibach. Could you bring Slovenia closer to us in that context?

Laibach: We could and we probably did, but we are not really a Slovenian group by definition and promoting Slovenia is not our task. We only live and work in this country, which accidentally makes us being part of the nation with the best location.

Laibach: We could and we probably did, but we are not really a Slovenian group by definition and promoting Slovenia is not our task. We only live and work in this country, which accidentally makes us being part of the nation with the best location.

5. Laibach was so controversial that your shows were banned, even to use the name Laibach itself. Was that too a part of Laibach’s statement? How was your message still heard despite the bans?

Laibach: Yes, the name was always a part of our statement and because of the ban it was heard and discussed even more. Same goes for the shows that we were banned to do. Those were basically our best and loudest shows.

6. Were you trying to manipulate public opinion or was it more about raising awareness about certain subjects? Would you say that Laibach was a herald or even a catalyst of the wind of change that led to breakup of Yugoslavia?

Laibach: Of course, we were manipulating public opinion, that is what we do. And of course we are not responsible for the breakup of Yugoslavia – we loved that country – but yes, we were a herald and to the certain extent even a catalyst of the wind of change that led to breakup, we cannot deny that. Anyway, the country would fall apart also without us doing what we did.

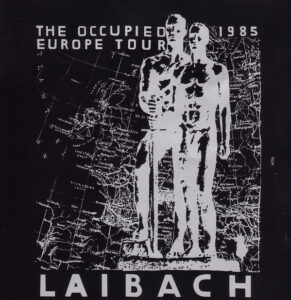

7. What inspired the Occupied Europe Tour? What message were you trying to convey with the name of the tour and also with your appearance in Yugoslav army uniforms?

7. What inspired the Occupied Europe Tour? What message were you trying to convey with the name of the tour and also with your appearance in Yugoslav army uniforms?

Laibach: The Occupied Europe Tour 1983 was inspired by the then still divided and militarily occupied Europe and we wanted to underline this fact with the title of the tour. The Yugoslav army uniforms that we wore, were there to express the militant nature of popular culture that we were practising and representing. The fact that we wore military uniforms of the declared non-aligned Yugoslav army only added to the fun, but also helped us to move freely through both ideological blocks.

8. Your visual expression has always been a vital part of Laibach. How was your visual identity created and how did you feel about reactions to it? How did you make the existing totalitarian and industrial aesthetics work for you?

Laibach: It came to us naturally; we copy-pasted everything around us, putting it into our, laibachian, context. Every aesthetics is basically totalitarian as soon as it is defined, becoming a canon and/or it is practised industrially.

9. What was the role of the NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) and what was behind the idea of the NSK utopian state?

Laibach: In order to answer you to this question we need to clarify some facts and notions first. There was the historic NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) and there is the NSK State. Neue Slowenische Kunst is not the same as NSK State; these are two very different notions – as you are already indicating yourself in your question. Laibach started in 1980 and Neue Slowenische Kunst was created in 1984, more or less as a result of the ban on Laibach, that lasted between  1983 and 1987 and because there was a lot of people from different media who wanted to ‘connect’ their work to Laibach. Therefore, we decided to create a kind of expanded Laibach, consisting of different groups, specialised for theatre, art, design, architecture, philosophy, etc. within one larger collective, primarily based on ideas and aesthetics, established in 1982 Laibach manifesto. Yugoslavian political and cultural situation gave a perfect background for this movement to happen. NSK successfully functioned between 1984 – 1992, when it started to disintegrate as a formation and finally ceased to exist, proclaiming as its final act the constitution of NSK State – a virtual State in Time (or State of mind), with no borders and no physical territory, but this time operated directly by its thousands of citizens from around the world. The utopian transnational State (without its own territory) was an old idea that Laibach started back in 1982 and formation of Neue Slowenische Kunst was the first step towards it. Today historic NSK does not exist anymore, only the NSK State does. As one of original creators of the State Laibach generally still supports its idea, but we are not involved actively in its manifestations anymore. Our opinion is that such State should in principle be able to exist independently from Laibach as well as from other NSK State founders.

1983 and 1987 and because there was a lot of people from different media who wanted to ‘connect’ their work to Laibach. Therefore, we decided to create a kind of expanded Laibach, consisting of different groups, specialised for theatre, art, design, architecture, philosophy, etc. within one larger collective, primarily based on ideas and aesthetics, established in 1982 Laibach manifesto. Yugoslavian political and cultural situation gave a perfect background for this movement to happen. NSK successfully functioned between 1984 – 1992, when it started to disintegrate as a formation and finally ceased to exist, proclaiming as its final act the constitution of NSK State – a virtual State in Time (or State of mind), with no borders and no physical territory, but this time operated directly by its thousands of citizens from around the world. The utopian transnational State (without its own territory) was an old idea that Laibach started back in 1982 and formation of Neue Slowenische Kunst was the first step towards it. Today historic NSK does not exist anymore, only the NSK State does. As one of original creators of the State Laibach generally still supports its idea, but we are not involved actively in its manifestations anymore. Our opinion is that such State should in principle be able to exist independently from Laibach as well as from other NSK State founders.

10. Did you feel that the cultural institutions failed to recognize new ideas in the 80s? What’s the long-term impact of NSK on the art world of Slovenia?

Laibach: Some institutions recognised new ideas in the ‘80s but not all of course – which we take as a compliment.

The long-term impact of the NSK movement on the art world in Slovenia, and also wider, is probably the recognition that impossible is possible, even when it’s not.

11. You often reinterpreted popular music and attached different connotations to the original ideas. The cover versions often became provocative twins of the original songs. What was the criteria for choosing songs you’d cover? Can you bring that process closer to us?

Laibach: We always find existing songs of other artists potentially relevant historic material that could be or need to be re-interpreted. In principle we choose songs that help us telling the specific story. The criteria of choosing differ from project to project and the process is always triggered by different elements and contexts. The context of interpretation is very important and today there is often more originality within the context itself than in the content. But sometimes the history of a chosen song is also an important factor and new interpretation only makes sense in relation with historic context of the existing song; most of all we are interested in those songs that are having (and hiding) certain schizophrenic character, something in a manner of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and can bring out the hidden content, the hidden reverse. In fact, we don’t even search for songs much; the right ones simply find us by themselves.

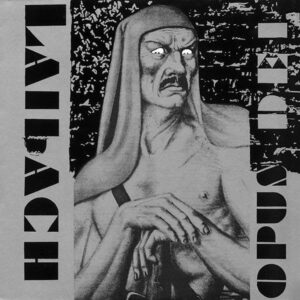

12. Speaking of cover versions, a cover of Queen’s “One Vision” appeared on your album Opus Dei, which brought Laibach a commercial breakthrough. With so many changes on the geopolitical map just a couple of years later, what were you trying to point out with “Geburt einer Nation”?

12. Speaking of cover versions, a cover of Queen’s “One Vision” appeared on your album Opus Dei, which brought Laibach a commercial breakthrough. With so many changes on the geopolitical map just a couple of years later, what were you trying to point out with “Geburt einer Nation”?

Laibach: Geburt einer Nation (The Birth of the Nation) does refer to the great silent film drama, directed by D. W. Griffith, telling the story of a birth of the modern American nation, but it also anticipates the somewhat similar events that were happening in Europe at the end of the ‘80s and beginning of the ‘90s, including the reunification of German nation and the birth of new national states on the Balkans. Especially on the Balkans – but not exclusively – the birth of new states and new identities resulted in bloody wars and the rise of new nationalism that is well and clearly contextualised in this – originally Queen’s – innocently entertaining pop song.

13. You even crossed paths with Opus Dei, the institution of the Catholic church. Were you surprised that they wanted to take legal action against Laibach for the use of the name Opus Dei for your album?

Laibach: Yes, this controversial catholic organisation tried to ban our album, titled ‘Opus Dei’ in 1987, way before themselves received world attention as a result of Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code and the 2006 film based on the novel. We were not too surprised with their intentions, in fact we were quite flattered. It would be much stranger if they would not react at all. But they were not succesfull with their ban; album was still sold, even if in some shops only bellow the counter.

14. What has been your position on the dogmatic and highly structured nature of church as an institution?

Laibach: We’ve learned a lot from church as an institution, also that it has nothing much to do with God him/her/it/self. Still, it’s a good place to meditate and listen to silence. The problem is when people are trying to exchange their personal misery in churches for deliverance of faith and their prayers are heard only by the devil.

15. Your expression is assertive, provocative, unapologetic and even harsh. Do you think that more aggressive approach to certain subjects is sometimes necessary to get the message across?

Laibach: We live in times of intense information overload when people don’t really listen anymore and they try to understand even less. The basic mode of social communication is in principle aggressive. We’d love to practice a different, less assertive approach, but it’s a luxury that we can’t afford, unless we speak softly and carry a big stick along.

16. How did you feel about being named as the most dangerous group in the world by the English press?

Laibach: We felt humbled and scared; we hoped we wouldn’t do something dangerous to ourselves.

17. What in your opinion lead to international success and recognition?

Laibach: We can’t deny that we had a very stubborn strategy – which actually worked to some extent – but at the same time we also very much ignored the market rules. Probably it was again the question of time in the ’80s that was right and perceptive enough for Laibach. Plus, we had some good ideas too of course…

18. You were an inspiration to other notable groups and new generations of creatives and artists. What do you think Laibach means to the world and your home country in that sense?

Laibach: Nothing really; true, many groups from different genres and also many other creative people and diverse artists have expressed their affection for Laibach. Also, time has confirmed many of our assumptions and predictions and some people may respect us even only for the music. But nonetheless, it constantly seems to us that we are completely irrelevant in what we do and that we are still nothing else but absolute beginners. Nowadays core values have totally lost their meaning and we do what we do just because we don’t know otherwise. And that’s in principle the best way – if not the only way.

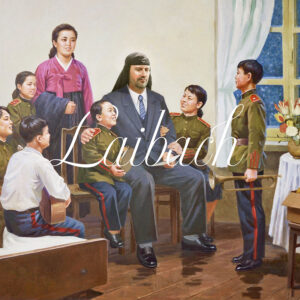

19. Last time I saw you was in March 2019 at Shepherd’s Bush Empire in London on your The Sound of Music tour. Before the show there was a documentary about your performances in North Korea. Could you summarise your experience? What have you learned from it?

Laibach: We’ve really talked a lot about North Korea and our experiences in this country already, and there’s also a film about it … Basically, North Korea is, in some perverted way, a purified version, an unfiltered, stripped down reflection of life that we live in so called Western democracies. This is much truer than we dare to admit. Of course this is a matter of simplification, but the West is also largely simplifying its understanding of North Korea, which is in fact a prisoner of a practically unsolvable political situation – as long as China and USA hold the Korean cards in their hands. We honestly wish North Korean people good luck on their way into the future, but maybe their future – if they ever step into it – may be worse than the life they are forced to live now.

20. Have you ever considered yourselves brave for speaking about certain subjects or playing in certain places, for example Sarajevo just before Dayton Agreement?

Laibach: No, we do not consider ourselves particularly brave. Lucky maybe, but not brave. We spent only a few days in Sarajevo towards the end of the war, while the citizens of Sarajevo were there all the time, all 1425 days of siege, the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare. It lasted three times longer than the Battle of Stalingrad and more than a year longer than the Siege of Leningrad.

21. As for your work, was sparking controversy more intuitive or thoroughly thought out?

Laibach: If you read our manifesto from 1982, then you will understand that we decided on controversy very much programmatically, but without good in situ intuition such controversy is of course not possible in practice.

22. How did you manage to stay apolitical as a public group which has been addressing political and societal subjects through its work?

Laibach: We had to stay apolitical if we wanted to be politically creative and socially sensitive. If we’d really want to deal with concrete politics, then we’d have to get into it totally, accepting and dealing with all its banality and formality, and not just the creative side of it. Politics is a dirty job, and somebody’s gotta do it. But not Laibach!

23. Were there situations when you absolutely couldn’t predict the outcome or reactions of the wider public, critics or institutions?

Laibach: Many times; the relation between us and audience, wider public, critics and institutions is usually tense, like a good game of chess. And that is precisely how it has to be, otherwise it makes no sense.

24. While one can say that Laibach has always stayed a group of four core members, it’s also been an open platform to different collaborators. How did that concept work for you over the years?

Laibach: We theoretically developed the idea of membership and collaborators already in our 1982 manifesto and we practised it successfully to this day: “LAIBACH works as a team (collective spirit), according to the model of industrial production and totalitarianism, which means that the individual does not speak; the organization does. Our work is industrial, our language political. The quadruple principle (Eber – Saliger -Keller – Dachauer) conceals in itself an arbitrary number of sub-objects (depending on the needs). The flexibility and anonymity of the members prevents possible individual deviations and allows a permanent revitalisation of the internal structure. A subject who can identify himself with the extreme position of contemporary industrial production automatically becomes a Laibach member.” Of course, this does not make us John – Paul – George and Ringo, but we are not very far from them either, except that there is more of us that can jump in and rotate, similar like politicians rotated on power in Yugoslavian self-management system, especially after Tito’s death.

25. Having lived in Yugoslavia, later sovereign Croatia and presently United Kingdom, I noticed that audiences see Laibach through different prisms, depending on their own geopolitical and historical backgrounds. How easy or difficult is it to communicate your ideology to different audiences across the globe and how important is it for you that they understand your work in its entirety?

Laibach: It is important for us that people participate with their understanding. What we communicate is universal, although it is not exactly that radically consumable as Coca-Cola. Therefore, there is no wrong understanding of Laibach, every understanding is correct. But the best and most precise understanding is actually the misunderstanding itself.

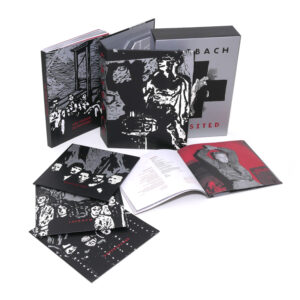

26. Last year, for your 40th anniversary you released Laibach Revisited, a limited edition set. What’s next for Laibach in 2021 and further?

Laibach: Very soon we are releasing another historic live recording of a show that we did in fabulous Reina Sofia – Museo Nacional Centro de Arte – Spain’s national museum of 20th century art. This concert was actually a re-enactment of a super controversial 1983 show that we did at Zagreb’s 12th Music Biennale. After that we are publishing music that we created last year for the theatrical production in Berlin, based on Heiner Müller’s work. Also, this year we are finally releasing original soundtrack music that we did for the Iron Sky – Coming Race sci-fi film, including lots of additional material. Several more albums are waiting in a line after that and yes, we are also already working on very interesting new projects.

Find Laibach Revisited here.

Visit Laibach shop here.

Check future events here.